- Home

- Tony Fernandes

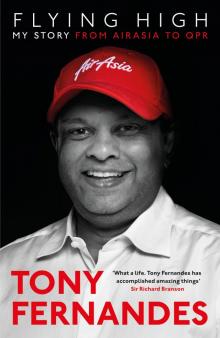

Flying High, My Story Page 7

Flying High, My Story Read online

Page 7

Today I am always keeping an eye out for such moments – edgy innovations that point to seismic shifts. Whenever I sense AirAsia or any of my other businesses is becoming heavy-footed and can’t anticipate or respond quickly to new technology, I worry. Business is about agility and being able to move without being weighed down by processes, committees and working groups. There are too many examples of successful companies being brought down by their lack of awareness or nimbleness when technology or the market changes – look at Kodak or Nokia and a lot of retail outlets who didn’t embrace changes in technology which threatened their traditional products. In business you have to be aware of these developments and you have to respond.

Leaving Warner was the right thing to do not only because the industry refused to innovate but also because I was starting to lose interest, and my own performance started to falter because of it. I’ve always tried to ‘be the best, do the max’ but I reached a point where I couldn’t do anything more for the industry even in the position I was in. This was problematic for me because I’m a strong believer that you should earn and deserve your salary every single day. It was one of the things that confused me when I took over QPR and saw players who were earning a fortune but weren’t giving everything to the game. I personally don’t understand how anyone can draw a salary and not fully commit to their job. When my performance was dipping because I didn’t believe in what I was doing, I knew I had to go.

I sat down with the senior team at Warner in early 2001 and we agreed a severance package. I negotiated with them to let me keep my office space in the Warner building in MUI Plaza, Kuala Lumpur, along with my brilliant assistant, Kim, and my company car. I thought my office would be useful to retain for whatever new adventure lay ahead; from their side, they realized there were a lot of loose ends to tie up, so they felt it would be to everyone’s advantage that I kept it.

Though I loved my time in the music industry, I felt good about leaving Warner. Along the way I’d met some great people, including Din, Kathleen Tan, who ran Warner Singapore after joining as regional head of marketing, Tassapon Bijleveld, who was CEO of Warner Thailand, Sendjaja Widjaja in Indonesia, Marianne ‘Maan’ Hontiveros in the Philippines and many others. We had farewell parties in each of the countries, and at each they made sure that they played two songs: ‘Thank You for the Music’ by ABBA and ‘I Believe I Can Fly’ by R. Kelly. One looking back and one forward. When I made my farewell speech in Indonesia, I looked forward and said that one day they’d all work for me again. Turns out I was right.

The final meeting with Warner was in New York and, when it was over, I flew to London. I didn’t really have a clue what to do. I didn’t think I had the balls to become an entrepreneur but I’d asked around half-heartedly in the music business and there weren’t any openings that tempted me. When I first landed my job at Virgin and then at Warner, I had thought I’d die working in the music business because I loved it so much, but now it felt a bit stale and I sensed there were other things I could do. I just had to find them.

When I returned to London, I was at a loose end. One afternoon in February 2001 I made my way to the Spaniards Inn, a famous old pub on the edge of Hampstead Heath. I was sitting there nursing a sparkling water when I saw Stelios pop up on television. I knew he was the founder of easyJet, the orange-branded low-cost airline that was growing so quickly in the UK. As he was being interviewed, I leaned in closer.

5. Daring to Dream

Soundtrack: ‘I Believe I Can Fly’ by R. Kelly

A few things came together in my mind in that pub, when I was listening to Stelios speak. I loved aeroplanes, airports and the aviation business. I was great at marketing and promotion. There were no low-cost airlines that I knew of operating in Asia.

I had to see for myself. That very afternoon I jumped on a bus at Hampstead to Brent Cross shopping centre, and there I made a connection with a 757 Green Line coach to Luton Airport – the same coach company that delivered me to Epsom, and that Charlie Hunt and I used to take to Heathrow twenty years before.

I walked into the terminal and was blown away. It felt like the entire airport was easyJet branded – orange was everywhere. Passengers flying off to Barcelona for £8 or Paris for £6 looked so happy. The whole operation was impressive, from the blanket branding of the airport to the simplicity of the offer.

I decided I was going to start an airline. The words I’d spoken to my mum on the phone all those years ago came back to me: I was going to make it affordable to fly from Kuala Lumpur to London. Before I left Luton I bought a Handycam and filmed everything so I could remember every detail of the operation, from the easyJet branding at the entrance, to the airport building, to the uniforms of the check-in staff. I loved the overwhelming brand feel that passengers got from the airport.

As it happened, I got a call from Din soon after. He was stuck in some remote place on the Iraq–Turkey border and needed help getting a hotel room and a flight back. We’d kept in touch throughout my Warner days and I got him good corporate rates for travel. When he called, I asked him what he thought about setting up an airline. He sounded enthusiastic but had a more pressing concern.

‘Sure, sounds great. Now can you get me that deal on the hotel room?’ Din is never one to pass up the chance for a discount.

I flew back to Malaysia and Din and I met to discuss the basic plan, which was to provide low-cost long-haul flights to a European hub airport; we would then link up with easyJet or Ryanair for onward connections within Europe. He liked it. Din shared my enthusiasm for airlines and travel and wanted to do something different.

We agreed that we wanted to be independent, apolitical, and that we wanted to create something totally new. Our style of working together was pretty clear too: I would be the front man, doing the marketing and publicity, and he’d do what he called the ‘boring stuff in the background’.

Din and I have a true partnership. We each focus on what we’re good at and play to those strengths. As a result, not much gets past us. We also agreed there and then that this was something we would build up, and put everything into it to succeed – not just get into it to make a quick buck. I said, ‘Let’s build a real business with actual profits that we can plough back in to drive growth. So, in years to come, we can look back and see something good that we’ve created.’

He was on board with that. He wanted to split the business 50/50 but I insisted on the extra 1 per cent because it was my idea.

At that point, still influenced by my love of music, I came up with the name Tune Air for our new airline project and decided on orange as the brand colour (I cared less about borrowing Stelios’s orange than I did about being accused of copying Richard Branson’s iconic red! Although I was quickly told by many people – pilots, government ministers and friends – that I should change to red, which has always been my preferred brand colour.) The details of the operation could have fitted on a napkin at this stage and the really pressing question was the one facing most entrepreneurs every time they try to launch something new: how do you start a business if you know nothing about the industry?

The only answer I had was to do something I was very good at: talking to people. I called people in my address book. Pretty much everybody laughed at the idea of me running an airline. So I rang Epsom and asked to be put in touch with anyone connected to the airline business. As always, Epsom were helpful and offered three people: Sir Brian Walpole, who was one of BA’s most well-known pilots and had been the Queen’s Concorde pilot; Clive Beddoe, who was one of the founding shareholders of a low-cost carrier called WestJet based in Canada; and my old Holman House mate, Mark Western, who was now a lawyer involved in aircraft leasing. I called Mark and asked him whether he could introduce me to Stelios to talk to him about my idea. Mark thought that that was probably a waste of my and Stelios’s time because Stelios was on a different mission, but he did suggest I speak to GECAS (GE Capital Aviation Services) – the aviation leasing arm of GE and one of the bigges

t in the industry, with a fleet of nearly 2,000 planes leased out to airlines in seventy-six countries.

Nonetheless, I did write to Stelios because I admired what he’d done. He replied with a nice email and a polite refusal to get involved. I guess the success of my efforts in the aeroplane industry have proved his decision wrong, but I learned something important from the exchange – he did at least reply. Now that I’m in Stelios’s position and get thousands of notes, emails and messages on social media from within and outside the company, I make sure that I go through every single one. Some of the great projects and ideas that we’ve come up with and seen through to execution have come from people getting in touch with me by email. It’s a key part of company culture: you have to create an environment where people aren’t afraid to share their ideas. So many flying routes, for example, have been introduced to AirAsia because staff have come forward and suggested there’s a need for them.

When you receive countless ideas and requests from people it’s easier to say ‘no’, but you never know what opportunity may come up. If Stelios had invested in me he could ultimately have part-owned a major Asian airline. So I always take cold calls or emails seriously; I investigate every single one of them. Some ideas might be preposterous but others can contain the germ of something special.

Our first attempts at sketching a business plan were chaotic, to put it mildly. We kicked off with a frenzied period trying to learn as much about the industry as we could, desperately trying to work out how much money we needed and how big a team could get our idea off the ground.

I based myself in the familiar surroundings of my old Warner office in Kuala Lumpur. I started to meet and talk to people to fill in the blank spaces in my understanding of what running an airline actually involved. In the first few months, Din and I hired a CFO, Rozman Bin Omar, and an accountant, Shireen Chia, and tasked them with working on the financial model. Din and I were the two main shareholders but even with my pay-off from Warner I was nowhere near as financially viable as I should have been. I roped in an old music industry contact, Aziz Bakar, as the third shareholder.

The office in Kuala Lumpur, a room that would be spacious for a single senior executive, was starting to feel a little cramped. I bought self-assembly desks when new people arrived and we ended up with a room stuffed with an odd selection of desks and chairs. It was chaos, and we took to calling it the War Room – many schemes were hatched there in our stealth operation to conquer the international airline industry.

We threw ourselves into the idea, going out to meet companies like Petronas, Malaysia’s main oil and gas company, to negotiate fuel prices for planes and routes we didn’t have. Mostly people laughed at us and said, ‘Come back when you actually have a plane.’ But we persisted, working round the clock, researching, calculating costs for parts and services that we didn’t yet need; trying to understand the airline business and all the while adapting our model.

On Mark Western’s recommendation I had connected with John Higgins at GECAS. Hoping that he’d be able to offer some advice, I sat down with John and outlined the plan which I’d developed so far: I wanted to lease Boeing 767s to fly to London from Kuala Lumpur. I think he thought I was a failed rock star with far too much money on my hands, but he was good enough to listen and make two important introductions. That meeting was the start of a relationship that has been crucial to AirAsia’s success and one of the most satisfying business partnerships I’ve ever had.

The first introduction was to a man called Conor McCarthy. With over twenty years’ experience in the airline business, he’d recently quit as Director of Group Operations at Ryanair to set up his own aviation consultancy. The second introduction was to Mike Jones, who was GECAS’s representative in South East Asia. We clicked as soon as we met; Mike has been with us since that first introduction and remains a trusted advisor, colleague and business partner. He gave us a big break when we started out and has been the one with whom we’ve done pretty much all of our deals.

It was shortly after my meeting with John Higgins that I rang Conor McCarthy and was greeted by a thick Dublin accent.

‘Hi, Conor, it’s Tony Fernandes. I think John Higgins might have mentioned me to you?’

‘Ah, sure, Tony. You’re looking to start a low-cost airline? You’re probably only the fifth person who’s had the idea in the last six months!’

‘I think I can make it work. I’m just putting together a business plan. Can you come out to KL to help?’

‘Sorry, mate, I can’t come all that way. Tell you what, if you’re serious, meet me at Stansted Airport and we can have a chat.’

Five days later, there I was standing at the Hertz Rent-A-Car desk. Sometimes people think that the origins of huge businesses can only take place in posh hotels or luxury resorts, but that’s really not the case.

My phone rang. It was Conor.

‘I can’t see you. Where are you?’

He didn’t know much about the world – he’d probably never been west of Galway or east of London – and from my name and my accent he probably had the idea that I was some six-foot, suave Antonio Banderas figure because he clearly didn’t think I was me when he first saw me.

‘I’m the short, fat Indian guy standing right in front of you.’

That broke the ice.

We sat down for coffee and I presented him with the business plan that we had so painstakingly drawn up. It was a pretty professional-looking document, neatly ring-bound, with tabs and indexes. We had put a lot of effort into it. But the thing about Conor is that he doesn’t pull his punches – he describes himself as coming from the Ryanair School of Diplomacy. After about twenty seconds, I saw why.

‘It looks great but the concept is crazy. Do you think you’ll persuade Michael O’Leary [the owner of Ryanair] and/or Stelios to agree to supply and take passengers flying to and from Malaysia from their networks in Europe? That they’d agree to feed you passengers and allow your passengers to access their routes? Why would they do that?’

‘They’d make more,’ I argued.

‘No, they wouldn’t.’

I needed to understand why he was so definitive.

‘Why wouldn’t they?’

‘Well, they already fill most of their planes – their load factors are very high – and this would complicate their business model. They would have to work out a whole new business concept in terms of transferring baggage, the accounting model in terms of who gets the money, in terms of passengers who are delayed or who miss their flights, who puts them up in a hotel, and so on. All of that complication you’re pitching to a couple of guys whose automatic reaction will be, I don’t need this, I’ve got 90 per cent load factors and the business is doing fine. Secondly, why would they talk to you? You’ve got no experience in the business. They’d just as soon turn round and say, If I’m going to do it, I’ll do it myself, not with you.’

I was reeling but saw that he was right and our plan was hopeless.

Conor is a positive guy, though. He looks for solutions not problems. He went on.

‘Tell me, how many people live in Malaysia?’

‘About 27 million.’

‘OK, so what are you worrying about? Just go set up a low-cost carrier in Malaysia that looks just like the models in Europe; stop trying to invent something new. These guys have made a load of money doing things simply. Sell your tickets over the web; don’t use travel agents; get a single-class operation; put as many seats in the aircraft as you can; use the same type of aircraft; fly the planes morning until night and have the engineers work on them overnight. Be pure low cost.’

It was like the scales fell away from my eyes. Of course, all the airlines in South East Asia were charging an arm and a leg for travel and, as a consequence, very few people flew. A low-cost airline would democratize and revolutionize aviation in the region. In my dramatic way – and because after just two sips of coffee I trusted him – I took my carefully constructed business plan and ripped it in half

in front of him.

‘Let’s start again.’

Even so, that early dream of fulfilling my promise to my mum to make it cheap to fly to London wasn’t easily dismissed. I said to Conor the idea of low-cost long-haul would remain in the bottom drawer. I promised that one day I would properly explore it – which eventually I did, with the launch of AirAsia X.

Conor’s experience at Ryanair was invaluable and I decided that we needed him on board as quickly as possible. Din and I reworked the business plan and I incorporated as much as I could from my meeting with Conor. We sent it off to him after a week, inviting him to come and help us.

I offered to pay him half in shares and half in cash, as we had no money. But he said no, he’d take it all in cash. Perhaps he didn’t believe in the enterprise as much as Din and me.

Conor came out to Malaysia, and we carefully started to reconstruct the business plan. With him on board, things started to come together over spring and early summer 2001. We were building a financial platform, identifying areas we needed to research and find experts in, and we built connections with GECAS to supply us with leased planes. It started to look like we might have the basics needed to launch an airline.

One morning, Aziz, Din and I were on our way to a meeting at the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs in Dayabumi, Kuala Lumpur. I was reviewing our progress and feeling pretty optimistic before I suddenly had one of those thoughts that makes your stomach turn.

‘We don’t know how to get an airline licence,’ I said.

We looked at each other and slumped back in our chairs, before Aziz said some words that are common in Malaysian business.

‘We need political connections. And we have none.’

Then I had a brainwave. We were about to meet Dato’ Pahamin Ab Rajab. He was the secretary-general of the ministry; we’d worked together to take on the music pirates when I was first at Warner in Malaysia. Before that he’d been in the Ministry of Transport. He was one scary guy – a man of fierce, passionate temper but honest and straight. Exactly the kind of person I like, in other words.

Flying High, My Story

Flying High, My Story