- Home

- Tony Fernandes

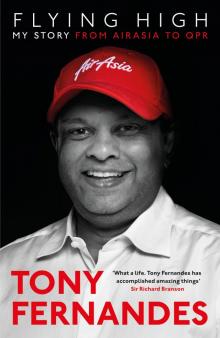

Flying High, My Story

Flying High, My Story Read online

Tony Fernandes

* * *

FLYING HIGH

My Story: From AirAsia to QPR

Contents

Prologue: A Tuck Box of Dreams

1 About a Boy

2 Outward Bound

3 The Wilderness Years

4 My Life in Music

5 Daring to Dream

6 Flying High

7 Tragedy Strikes

8 The AirAsia Journey

9 Ground Speed

10 We Are QPR

11 The Beautiful Game

12 Tuning Up

13 Apprentice Adventures

14 Now Everyone Can Fly

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Follow Penguin

To the two most wonderful humans I helped create, Stephen and Stephanie. Continue being the most down to earth and caring people I know. Thanks for always being there for me.

Prologue: A Tuck Box of Dreams

Soundtrack: ‘Dreams’ by The Corrs

A few years ago a friend from my schooldays, Gerry Wigfield, rang out of the blue. Even at the other end of a long-distance phone line I could hear that he was excited.

‘Tony, my mum’s found something of yours.’

‘What is it, Gerry?’

‘Ah, that’d be telling. I’ll get her to send it to you when you’re next in London.’

I was staying in Kuala Lumpur for several months on business, so I admit that this conversation soon slipped my mind. A few days after I eventually arrived back in London and settled in my house in Chester Square, the doorbell rang. I padded to answer it dressed in my pyjamas, not really thinking about who or what might be waiting behind the door.

Standing there was our postman holding a parcel about three feet long by a foot high, wrapped in brown paper, with my name neatly printed on a white sticker. As he passed the box over I braced myself for something heavy, but it was surprisingly light. I put it down on a table in the hall, signed for the delivery and shut the door. For some reason the memory of Gerry’s call came back to me and I ripped off the packaging.

A few seconds later, standing in a mess of brown paper, I started to well up. I was looking at a battered blue cardboard chest with reinforced leather corners, brass locks and a leather strap at the end. It was my tuck box from my secondary school, Epsom College. I hadn’t seen it for about thirty years.

On the lid of the box were three stickers: the badges of West Ham United, Qantas Airways and the Formula One team Williams.

I snapped the locks and lifted the lid. Inside were two C90 cassette tapes: Abba’s Arrival and Steely Dan’s The Royal Scam, as well as a packet of the dried noodles that my mum used to send me from Kuala Lumpur. The contents of the tuck box tipped me over the edge. I was a wreck. Memories of Mum, moving to England and my school life flooded over me.

The tuck box, inside and out, represented all the dreams I’d had when I was growing up: I loved sport, I loved music and I loved aeroplanes. What was so overwhelming for me in that moment was realizing that my childhood dreams had become my reality.

Since leaving Epsom, I had headed up a music business, partied with some of the biggest pop stars in the world and brought Malaysian and Asian bands to the global stage.

I had taken over an English football club and been carried on the shoulders of the players on the Wembley pitch after we won promotion.

I had stood on the starting grid at a Grand Prix with my own Formula One car.

I had acquired a tiny airline and transformed it into an international business carrying 70 million passengers a year.

Turning those dreams into reality – the journey from putting stickers on my tuck box to opening the door to the postman some thirty years later – has been nerve-racking and heartbreaking at times, but packed full of excitement and joy. It also makes for a pretty unlikely and wildly unpredictable story.

But let’s start at the beginning, where my early life and school career didn’t show any signs of those dreams coming true.

1. About a Boy

Soundtrack: ‘Georgia on My Mind’ by Ray Charles

I pushed ten cents into the coin-operated binoculars and scanned the horizon. Nothing. I swivelled the binoculars round to point at the apron, studying the old turbo-prop planes, the Malaysia–Singapore Airlines’ Fokker F27s and DC-3s, the Air Vietnam Vickers Viscounts and the tiny private Cessnas. I shifted again to look at the hangars beyond the runway, where planes were being worked on by the engineers. I turned back to look at the horizon. Still nothing.

‘Relax, Anthony, we’ve got another hour before she lands,’ said my dad.

We were standing on the viewing platform of Subang Airport, Kuala Lumpur. It was a humid day in July 1969, a few months after my fifth birthday. My dad, Stephen, and I were waiting for my mum to come home from another business trip.

It was the third time he had told me to relax. I nodded. The binocular lenses went dark, so I pushed another coin into the slot and turned my attention back to the apron. We stood side by side and silently looked out together.

Finally, the Fokker F27 came into view, a speck turning into the familiar shape, slowly growing in size and swooping in towards the runway. The moment the plane touched down, my attention switched to the doors. As they opened, I held my breath until I saw Mum appear and walk down the steps. She looked up at the viewing gallery and waved. I ran into the terminal building where I looked through the iron railings into the baggage hall below. As soon as I saw Mum pick up her bag, I set off again, sprinting down the stairs, timing my arrival so that I threw myself into her arms the moment she came through the arrival gate.

The scene sticks with me because airports were always happy places for me. Dad and I would make countless trips from our home in Damansara Heights to Subang to meet Mum, and they all ended with this warm feeling of being reunited with her.

A few years later, Dad and I started making trips to the Weld department store in Kuala Lumpur. It had a huge record department with wooden racks holding albums stacked vertically so that we could flip through the records from front to back. We would go there on a Sunday morning between church (which I hated) and lunch, which we normally had at one of those old colonial restaurants like the Station Hotel or the Coliseum.

On one occasion I was standing on tiptoe on a stool flicking through the albums when I laid eyes on a special record.

‘Dad, Dad!’ I jumped down from the stool (we were there so regularly that the staff called it ‘Anthony’s Stool’) and ran across to him as he looked through the Dean Martin section. In my hand I had an album that I held up to him.

‘Can we buy it?’ I asked hopefully.

He nodded. I was hopping with excitement. It was my first record: the Supremes’ Supremes A’ Go-Go. We’d heard ‘You Can’t Hurry Love’ on Patrick Teoh’s radio show the previous weekend and I’d been itching to get the album ever since. In the holidays, if I dusted and organized Dad’s records, I was allowed to play them on our Grundig stereo system. He adored the classics – Dean Martin, Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Sammy Davis Jr – all the singers from that golden era.

The music I associate with Mum is Chopin’s Nocturnes. I loved to listen to her playing these beautiful pieces on the upright Yamaha piano in the living room. As well as Chopin, she’d play Mozart and Beethoven, and whenever and wherever we moved to, the piano would always have its own corner. Mum arranged for piano and violin teachers to come to the house and teach me but if I was going to learn to play something, I was going to do it on my own or with my mum. Her musical talents and methods definitely rubbed off on me because, like her, I can pick things up by ear and I always preferred to learn like that.

When she put on a record,

Mum would choose an artist like Dionne Warwick or Carole King. She had more progressive tastes than my dad but the most influential thing was how much they both loved music. That has always stayed with me.

Another thing that has stayed with me is Dad’s love of sport. He would watch every single sport shown on television in Malaysia. He followed teams and events with intensity and was a tireless supporter of underdogs – whenever there was an uneven contest, he always sided with the least-fancied team or player.

He would take me to sporting events all over the country and together we watched many matches on the television. I followed Brazil from a young age. Their teams of the early seventies were unbelievable: Pelé, Rivelino, Jairzinho, Carlos Alberto. All of them were outstanding players and the 1970 World Cup side were arguably the best team in history. Dad and I would also watch Star Soccer, which showed English football games with a six-month delay. For some reason the games always seemed to feature teams from the Midlands (like West Brom, Wolverhampton, Birmingham and Aston Villa). It was horrific football – lumping the ball up to the centre forward, a scrappy midfield with no skill or tactics, muddy pitches and bone-crunching tackles. It was all about getting rid of the ball as quickly as possible without a hint of a bigger game plan. There was none of the elegance or style you got with the other teams I’d watched, like Brazil. The contrast in the way they played football couldn’t have been more marked.

Then, one day in 1974, I saw another Star Soccer game and my opinion of English football changed for ever. The match was Aston Villa against West Ham. I hadn’t seen the London team before and it was as if I was watching Brazil, only in the mud and greyness of Birmingham. West Ham played from the back and they had a plan and a style – passing the ball around to create openings. Trevor Brooking, Alan Devonshire, Frank Lampard, Pat Holland and, my favourite, Clyde Best. They had the skill and fluidity of the Brazilian superstars. I decided there and then that I’d support them.

Although I loved sport, I wasn’t really any good at it initially. At the age of eight, I bought my first football boots and decided that being a goalkeeper was the easiest position to establish myself in. As long as I was playing, I was happy. Then at about ten something changed – suddenly I could play.

For my birthday around that time, my uncle bought me a Philips shortwave radio. There were no live games on the television so every Saturday night I’d tune in to the BBC World Service and Paddy Feeny’s Sportsworld. The programme covered the afternoon’s English First Division matches. Of course, in those days they all kicked off at 3.00 on Saturday afternoon – there were no matches on Sundays. The radio had a couple of shortwave bands, medium wave and FM, and I had to hold it up at all sorts of weird angles to get a reception (the best place was next to the fridge). I thought, ‘Wow, what a piece of kit.’

Every weekend during the season, that’s what I’d do – Saturday nights were all about the football from 11.00 p.m. till 2.00 a.m. West Ham rarely featured as the live game but regular updates meant I could follow them. Plus I got Shoot! magazine for all the latest news. At the start of each season they included a wall chart showing each of the leagues and cut-out labels for each of the teams. Armed with these, I changed the league positions after the results came in every Saturday night. I had a favourite team in each league as well. Believe it or not, QPR were my ‘second’ team at the time. Gerry Francis, Stan Bowles, Mick Thomas and Rodney Marsh made the club almost as attractive as West Ham.

I was sports mad, like my dad, and we went to just about every sporting event we could in Malaysia. There’s a football competition called the Merdeka Tournament (Pestabola Merdeka) which used to happen every year. All the South East Asia teams played a series of games over the course of a week. One year – it may have been 1974 or 1975 – we didn’t miss a single game.

We’d also go to the motor racing every year, at a track at Batu Tiga, and watch Formula Two and MotoGP. It was three days of very noisy track racing that I lapped up. There were some legendary South East Asian and Japanese drivers: Albert Poon (later ‘Sir’) and Harvey Yap were my local heroes. I thought of those days as I walked to the track at the first Malaysian Grand Prix many years later, surrounded by the revving of Formula One engines. Just like the tuck box, the memory brought tears to my eyes as I thought about my dad and how he’d have loved to have been there to witness such a momentous event.

When the Hockey World Cup came to Malaysia in 1975 it was the first time a world championship of any kind had been held there; the whole country went mad for it. We went to every game. Dad supported India so I did too, though it got a bit awkward when India met Malaysia in the semi-final and beat them (after extra time), going on to win the World Cup. Of course, in those days, the pitches were grass, so when it rained and the games were called off they were rearranged for a morning during the week instead of the evening. On those occasions, Dad would be driving me to school and I’d pester him, ‘Let’s go, let’s go, let’s go. We don’t want to miss a match.’

Finally he’d say ‘OK’ and we’d go. He criticized me for being useless at school but he’d also take me to a hockey match on a school day!

Alongside his great love of sport and music, Dad was quite studious, reserved, disciplined and highly principled. He was a doctor working for the World Health Organization, in charge of the programme to eradicate malaria and dengue fever. He had started out as an engineer before switching to become an architect and then finally settling on medicine. His family were from Goa and were upper middle class, but he grew up in Calcutta and went to boarding school when he was five. He did well – excelled at sport – and graduated with distinction. After his medical training, he was sent to Malaysia and met my mum on a blind date. He never left.

I loved my dad and his dedication to the WHO programme, and his political ideas have had a huge influence on me. He was devoted to the idea of public health for the public good and wouldn’t go anywhere near private medicine. He was naturally curious, always wanting to know how things worked and wanting to understand the world – he bought every encyclopaedia known to man and made sure I read them. I didn’t love him for that at the time, but I think that’s where my curiosity stems from. I still have the first encyclopaedia he bought me: The Book of Knowledge published by Marshall Cavendish.

Funnily enough, I was at a convocation ceremony at MAHSA University in Kuala Lumpur in March 2017 and met a nurse called Ajimah Hassan, who had worked with my dad in the early seventies. She told me that he was small but athletically built (which I was too for a while, believe it or not). She also told me that he was a heavy smoker who loved his coffee – he would often come to chat to the nurses after work over a cup of Nescafé.

‘He was so approachable,’ she said, ‘all us nurses felt that we could talk to him about anything at all. It was more like having a sympathetic big brother than a boss.’

At that moment, I felt so proud of him, and so proud to be his son.

While my father was reserved, Ena, my mum, was outgoing and infectiously energetic. She loved talking and getting friends together for a party. The house always seemed to be full of music and people: the Ink Spots, Winifred Atwell and the Platters. One day she found out that the legendary singer-songwriter Ray Charles was in Malaysia. Those were the days when no one had any security so she rang him at his hotel, introduced herself and said, ‘We’re having a party. Do you want to come over?’ And he did. He made straight for the piano and played ‘Georgia on My Mind’ – the song still makes my spine tingle. Many years later, when I was president of Warner Music in Asia, I met Ray Charles when he came back to Malaysia and he remembered everything: my mum, the piano and the party.

Mum’s surname was also Fernandez – but with a ‘z’ rather than an ‘s’. She was born in Malacca and I think I inherited some of my entrepreneurial spirit from her side of the family. They were a lot less well-off than Dad’s: her father was a car salesman who, during the Japanese occupation in the Second World War, was regularly put in j

ail for communicating with the British. He was a risk-taker – just like Mum.

After she finished school, Mum became a music teacher at a convent school but then her sister introduced her to Tupperware and her entrepreneurial gene was triggered. The business model was simple: you invited friends and family over to show them Tupperware products and got commission on any sales made. It was popular and Mum loved it – why wouldn’t she? It allowed her to throw parties and be an entrepreneur at the same time. She was so good at it that she rose through the ranks from selling agent to running Tupperware in Malaysia. With the job she was always off on field trips to see reps or pitch new products and one day this brought about my first experience on an aeroplane, a trip to Penang on Tupperware business. We’d always gone on the ferry before – driven to Butterworth and then taken the boat across to Penang Island – but this time we flew from Kuala Lumpur to Penang. For a nine-year-old boy it was an unbelievable thrill.

After that we’d often go on trips to visit dealers around Malaysia, and we’d make up songs to motivate them. ‘Gotta Tupper Feeling Up in My Head’ was the name of one. I still write songs today – not about Tupperware – and that’s because of her.

Mum was the dominant personality in the house. She was at the heart of everything we did and drove us forward. She was determined I was going to be a doctor – the family story goes that as soon as I was out of the womb she hung a stethoscope round my neck. Even my first toy was a doctor’s kit. But later it was to become the source of a lot of friction between us.

Even as a kid I could see that Mum adored me. Dad was less demonstrative. When I was eleven, I was made captain of our school football team, and in one match I scored five goals against a Japanese team. Dad was watching, and when I came up to him at the end of the game I thought, ‘He has to praise me this time.’ But all he said was: ‘You’re a real hog – you didn’t pass the ball once.’ I was devastated. At the same time, he rarely missed a game. He was devoted, but he found it hard to verbalize his feelings and give any praise.

Flying High, My Story

Flying High, My Story