- Home

- Tony Fernandes

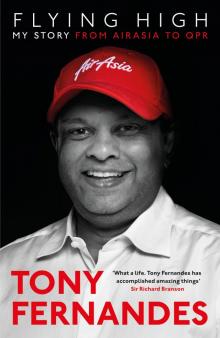

Flying High, My Story Page 3

Flying High, My Story Read online

Page 3

I said, ‘Mum, I want to come home.’

‘It’s too expensive.’

‘But it’s horrible here and I miss everyone.’

‘It’s too expensive, Anthony, you’ll have to stay until Christmas and come home then.’

‘But why is it so expensive? Why can’t they make it cheap?’

‘Flying’s expensive and we can’t afford to bring you home every seven weeks.’

I was angry.

‘Well, I’m going to make it cheap.’

It didn’t seem that big a deal at the time. I was furious that I couldn’t make it home to see my parents and friends, and could not understand that money should play such a big part in preventing my happiness.

Looking back, of course, this is when my idea – my lifelong mission – that everyone should be able to fly was first hatched. I instinctively understood that the cost of the plane ticket was the barrier to being with my family. I understood that not being able to afford to fly was a cause of a lot of unhappiness. I don’t think AirAsia would have been born if this seed hadn’t been planted decades earlier in Epsom.

The homesickness passed quickly after those first few testing weeks and within a couple of terms my life at Epsom was busy. I had a solid group of friends who shared my love of pranks; we played tricks on the teachers but also on each other, always mucking about in lessons and never taking them too seriously. There were the traditional challenges to take on, like climbing over Holman House, which involved escaping from a first-floor window, shimmying up a drainpipe, using as many window ledges and footholds as you could find, and then clambering on to the roof before reversing the journey on the other side of the house. When I look at the height and the difficulty of the climb now it makes me feel a bit sick. I’m sure the boys aren’t allowed to do it any more but back in the seventies no one really minded and, as it turned out, no one got hurt.

Best of all, there was sport to immerse myself in every day. Hockey was a big deal at the school and at least I understood that, having watched all those games with my dad and having played a bit with the boys back in Malaysia. In fact, Déj told me recently that when I started at Epsom he could tell I was a natural at hockey. I had good hand–eye coordination and although I was small I was also muscular so could hold my own when players tried to tackle me. As with football, I was quick and I had an instinct for goal. After one of the World Cup matches in Malaysia, Dad and I had approached the Indian team and I’d been given an autographed hockey stick (a Vampire) by the Indian captain. It was my pride and joy and I played with it at Epsom – making sure everyone saw the signatures.

Although I knew how to play hockey, we played it in the spring term at Epsom after rugby in the autumn had finished. And that confused me. I was used to playing hockey in the Malaysian heat, not the freezing cold with hands so stiff they were unable to grip the stick properly. The pitches were either waterlogged (meaning the ball constantly got stuck in the mud) or were frozen (meaning we all slid around). In my first winter term, it snowed. I was baffled – I’d never seen snow before. I asked a classmate how long snow usually lasted, and then I was even more confused when the white blanket disappeared overnight. Once, when the pitches were covered in snow, we were sent to the Epsom Public Swimming Baths. I was naturally expecting to swim but when we got there we found a maple-wood floor had been placed over the pool and we played indoor hockey on it. If anything, this was stranger to me than playing in the freezing cold.

In the summer term, cricket and athletics dominated our sports lessons. In my first couple of years I focused on athletics because I was a top sprinter – becoming Epsom School’s Champion at fourteen. Although I was short, I was lightning fast. Unfortunately, I never really grew; as the other boys’ legs got longer, mine stayed the same and I couldn’t match them. That wasn’t a problem on the rugby field because I was still quick and my size made me difficult to pull down, but over a straight hundred metres I didn’t have the stride length to match some of the bigger boys.

I got into cricket after that. It was one of those sports where I was either brilliant – scoring a century – or terrible – getting out first ball. There was rarely anything in between, which frustrated the Epsom sports masters. I had a strange batting action which meant that the backswing of the bat went out to the right and then forward rather than straight back and forward. Roy Moody, my house master and cricket coach, spent hours trying to correct the problem but I never learned. All it meant was that I found it difficult to ‘play straight’ – it didn’t stop me scoring a lot when I was on form but I often got bowled out needlessly. As it happened I had the same swing with a hockey stick but perhaps because I was usually in full flight when I went for a shot on goal, that mattered less.

Once I’d settled into the school, I found I was popular but I always felt there was a certain distance between me and the other kids. For the life of me I couldn’t work out why. One day, a good friend of mine, Charlie Hunt, a day student, invited boarders back to his home for a party. I was annoyed that I hadn’t been invited and assumed I wasn’t included because I was a different skin colour. When I asked him about it years later, it turns out that he hadn’t invited me because he thought I didn’t know how to use a knife and fork! He didn’t want to embarrass me because he thought I had grown up in a treehouse or something. At the time no one had heard of Malaysia – I used to say that it was between Singapore and Thailand and, even then, people couldn’t really place it. I do wonder whether, deep down, the shock of finding out that people knew next to nothing about Malaysia is one of my motivations for working so hard to put it and the whole Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) region on the map. AirAsia is certainly helping with that but it’s a slow process.

I did witness some clear instances of racism: the school was overwhelmingly white and the culture at the time was just different. Television programmes like Till Death Us Do Part and Love Thy Neighbour portrayed almost aggressively racist views, so it’s not much of a surprise that I was called names like ‘wog’, particularly on the rugby pitch. I don’t remember being offended or hurt, it just made me play better and harder. It’s as if the insults spurred me on to prove everybody wrong and I got more satisfaction from that than any other kind of reaction.

The academic atmosphere was quite intense at Epsom but the routine at school was good for me: having a predictable timetable brought stability and meant that I looked forward to certain parts of the day and the week. Breakfast was my favourite meal – there was an endless supply of horrific sausages that I’d wrap up in bread and wash down with a few bowls of cereal. After breakfast, we’d have a morning of lessons, which was the bit I didn’t particularly enjoy, but every day after lunch there would be sport – except on Wednesdays when we joined a branch of the service cadets of our choice. I chose the navy because the army guys were way too serious; the navy was where all the pranks and fun were to be had.

One Wednesday my friends and I broke into the navy store cupboard and I nicked one of each of the achievement badges and sewed them on to my cadet jersey sleeve. That afternoon, we had the big AGI (Annual General Inspection) parade in front of a rear admiral or some other high-ranking navy guy who was of course amazed by my accomplishments. He asked me all sorts of questions about how I’d got this or that award but I didn’t have a clue and had to bluff my way through. He gave up asking quite quickly.

As well as Wednesday afternoons, I enjoyed the weekends. After lessons on Saturday mornings, there were always matches against other schools in the area and, as I got older, I played rugby, hockey and cricket for Epsom.

On Sundays, full boarders were supposed to go to the chapel but I said I was Roman Catholic and that my dad didn’t want me to go to a Church of England service. The school would have allowed me to attend mass elsewhere but, naturally, I didn’t go; I just enjoyed some free time on Sunday morning.

I spent the weekends reading a pile of biographies and autobiographies; perhaps because, like

Mum, I am interested in people. Some of the books I read at Epsom shaped my outlook on life. The ones that really stand out and had the greatest influence over me were biographies of Alexander the Great, Thomas Edison and Robert the Bruce, and Antonia Fraser’s Cromwell, Our Chief of Men.

Alexander the Great became a hero of mine because he was so ambitious. He tried to create a world free of racial barriers and separate cultures by forcing ethnic groups to inter-marry. He believed in democracy and, above all else, he was a mummy’s boy! I was captivated by Thomas Edison’s life, inspired by the sheer number of ideas and innovations he produced. Studying his approach and life’s work illustrated to me the value of innovation, something that has influenced the way I run my businesses ever since. I constantly ask myself: ‘What do we need that we don’t have?’ ‘What could we do to make this easier for the passenger or customer?’ ‘What could the staff work on to change the way our business works?’ Like Edison, I never want to accept the status quo but try to find a new and better way of doing something. The main lesson I took from Robert the Bruce was the importance of tenacity and perseverance: he never gave up and I have the same determination in my work and life. Journalists often say that they tire of writing about my persistence as I pursue what I want at all costs. Finally, Oliver Cromwell’s republican views have had a meaningful influence on me; I believe that everyone should have a chance at life and if the system of government in charge gives one group of people advantage over another, that doesn’t seem fair to me.

Reading about and understanding these lives had a powerful effect as I passed through my teenage years. Some of the core business principles I run my companies by can be traced in part back to these books. I believe in a multicultural workforce based on meritocracy; I value persistence and admire it in people around me; and I am always looking to innovate in my companies, encouraging colleagues to come up with a new way of tackling a problem.

Through these men and their biographies, I really got the history bug; it’s still my favourite subject (even though the history teacher had been the one to shout at me on my first day). When I make speeches, I always look to the past to find my themes and examples. The lessons learned in those pages have stuck with me.

I still liked music but I only got to listen to it via the cassettes I borrowed from friends or had sent from home. I tracked down every musical reference I could out of sheer curiosity. When ABBA released ‘Fernando’ my friends thought it was hilarious to change the line to ‘Do you hear the drums, Fernandes?’ I sort of enjoyed the joke but got Dad to send me the album Arrival on cassette. Only to find it thirty years later, still in my tuck box.

My interest in music gave me a creative advantage and strength that some people lack – I was always on the lookout for new sounds, a trait which came to help me later during my time at Warner. Although never very happy in the classroom, I wasn’t a slouch academically; it was just that I was much more comfortable in the music room or on the sports fields where I was free to express myself. I played the piano as much as I could, though I still hated having lessons because I think I understood, even at that age, that I learned best by doing it myself. I pick things up quickly but I like to be able to see the immediate effect of what I’m being shown or taught; learning is an active and interactive process, and I learn particularly fast if I’m able to get my hands dirty. Most other subjects at school bored me because I couldn’t see the point of passive learning, which dominated the teaching style. I wasn’t interested in other subjects beside history and music; certainly not the sciences that were supposedly going to get me into medical school.

As I grew up at Epsom my main interests revolved around either sport, planes or cars (and sometimes the girls who’d just been admitted into the sixth form). There was a young biology teacher called Mike Hobbs who owned a Mini. One night we carried his car and put it on the centre line of the First XV rugby pitch. I can’t remember why we did it – perhaps because he’d wound us up particularly badly or just because we were in search of a good prank. We had a lesson with him the next day and we couldn’t stop laughing the whole way through it. Finally, he cracked and asked us what was so funny. We led him out to the rugby pitches to show him the car. Our laughter quickly turned to bewilderment and then panic as we saw that the car had disappeared. We had to explain what we’d done but had no explanation as to why the car wasn’t there. Class detention followed. The next day we saw Hobbs drive on to the campus in his Mini, smiling and whistling as he parked and got out of it. He told me much later that he’d heard us whispering suspiciously in the night and followed to see what we were up to. After we’d gone back to bed, he’d driven the car off campus and parked it in a neighbouring street so it would look like the car had vanished or been stolen. We had to admit he had out-pranked us.

Apart from staging pranks, I’d use my spare time to make trips to Heathrow as often as possible. Charlie Hunt and I would catch the 727 Green Line bus I took on my first day of school and we’d go plane spotting, watching the planes land from the viewing platform on the Queen’s Building. My interest in planes was growing and I loved being able to share my passion with someone like Charlie, who got it.

I sailed through school until my O-level year. In early January, with the new term just started, Dad called me. This wasn’t unusual: we’d been talking a lot more frequently since Mum had started going through another bad patch but his voice sounded different this time, quieter perhaps.

He said, ‘Mum’s really sick. It’s really, really bad. She might not survive this time.’

Even then, I didn’t take it too seriously because there had been other times like this when she’d been really ill. And Mum was a force of nature. Her energy was infectious when she was feeling well and those were the times I focused on. Her knack for entrepreneurship and business had created a huge success of the Tupperware job, so much so that she financed my education at an expensive English public school and provided a comfortable lifestyle for her family. But now there were real problems with her kidneys, which in turn seemed to be affecting her heart.

I called every day to check and the reports I got back were that she was getting better. Then, one day, I was sitting in a geography class – bored as usual – when the school secretary walked into the classroom and asked for me to follow her.

It was unusual to be pulled out of lessons so as I walked behind her to the school office I was dreading every step that took me closer to the phone. I picked up the receiver and was greeted by my dad, crying.

‘She’s gone,’ he said.

And with those words, my whole world collapsed. She was only forty-eight years old and I was only fifteen – at that age you think your parents are indestructible.

My dad, who had never really outwardly shown much emotion before, was still crying over the phone and, being so far apart, there was nothing we could do to help each other. I asked whether I should come home. He quietly said: ‘No, focus on your O levels.’

I’d spoken to Mum a few days before she passed away. She was concerned about my grades and the mock exams coming up but we hadn’t discussed her illness. In fact, the last time I’d actually seen her back in Kuala Lumpur, we had parted badly. We’d had a row because I’d told my parents that I wasn’t going to do physics, chemistry and biology for A level but had decided on biology, economics and history instead. The fallout turned into World War Three – my mum was angrier than I’d ever seen her before. When I left KL she was still pissed off with me and she just put me in a car and said ‘bye’ without a hug or any other sign of affection. In the end, they forced me to do the sciences but I told them that if they made me do them, I’d fail.

So the last time I’d seen Mum before she passed away wasn’t a happy memory and I didn’t get to say goodbye on the phone when we spoke either. It makes me sad to this day that the last time I actually saw her we parted on such bad terms.

I couldn’t stay at school while Mum was being buried thousands of miles away so I packed a

suitcase and went to stay with my Uncle John, Mum’s sister’s husband, in Braintree, Essex, for a week. I needed to be alone, out of sight of my school friends, and John was really good to me. He was strict – an old-fashioned English type who wouldn’t take any argument – but we grew close during that week. He had a huge room full of radio communications equipment, including radios you could use to listen in to the pilots’ frequencies as they talked to air traffic control. He was a bit of a plane-spotter too and I think we made a few trips to the airport that week. Staying in Essex with John was about the best thing I could have done to distract me from my grief. After a week, my uncle told me that I had better return and I reluctantly took the train to Epsom. Everyone at the school was good to me when I got back and my friends rallied round, trying to cheer me up.

After a difficult term, I travelled back home to Malaysia for the summer. The silence in the house was unbearable – without Mum there, we had no visitors, the piano was silent and there were no crazy schemes and plans. For the first few days I felt like I was waiting for her to come back to kick-start the life and noise in the house but then I realized that she wasn’t coming. So I decided to step into her shoes and did everything I could to make up for her not being there: inviting friends round, playing the piano, putting on records and trying to get the energy up. My sister was only two when I left for Epsom and was still young when I came back for the summer but that was the time when we started to bond properly.

As soon as I got back to school after the summer break, I transformed as a sports player from a pretty good all-rounder to something of a superstar. Up until O-level year I had been doing well across the board – in the A team for hockey and rugby and pretty good at cricket too. Then after Mum died I started channelling all of my grieving energy into my hockey boots and distracted myself through sport. I became the youngest player to play for the Hockey First XI, getting elevated from the Under-16s. The team were doing badly and, in my first match, a moment arrived when I was presented with an open goal. All I had to do was push the ball in but instead I took an almighty swing at it and missed the ball completely. I wanted the world to eat me up. But I redeemed myself in the final match of the season when I scored an amazing goal and had an outstanding game – my crimes earlier in the season were forgotten.

Flying High, My Story

Flying High, My Story